When you ask advocates why they become champions of a cause, it is usually because of some personal wake-up call. They, or someone close to them, has privately suffered from the condition they are now publicly fighting for. By this rule of thumb, we all should be nutrition champions. That is because every country has a serious public health problem and one in every three people is affected worldwide.

What is malnutrition? It's all around you. It's your friend's baby who just won't grow properly through lack of the right kind of feeding and care; it's your exhausted mother who does not have enough vitamins and minerals coursing through her veins; it's your father's blood pressure that is too high because of too much salt; it's your sibling who has diabetes because of too much sugar; it's your friend who cannot walk up the stairs to your apartment because his joints scream out in pain from carrying too much bodyweight because of an imbalanced diet and too little exercise.

It is too many early graves and it is too much lost potential.

It can seem like an intractable problem, but it is not. As the new Global Nutrition Report notes, the number of countries that are on course to meet global targets is rising quickly.

So what can you do to make malnutrition a relic of the past? Obviously, you can help get your friend and family member the support and help they want and need. But you can do a lot more.

First let's think about policymakers. It's pretty clear what they should do:

So what can you do to make malnutrition a relic of the past? Obviously, you can help get your friend and family member the support and help they want and need. But you can do a lot more.

First let's think about policymakers. It's pretty clear what they should do:

1. Demonstrate leadership from the very top. Nutrition improvement requires commitment, coherence and cash. Commitment because nutrition does not have a natural bureaucratic home. Is it health, agriculture, social protection, women and child development, education, water, sanitation and hygiene, climate change or food retailing? It is all of these things--a whole of society responsibility. So we need people who can see the bigger picture, who can bring together all the talents. Coherence is important because nutrition efforts will only be as strong as the weakest link and also because when, say, health and agriculture work together, they are more than the sum of their parts. Cash is needed to scale up nutrition actions--it is not sufficient but it is probably necessary.

2. Increase funding to implement nutrition actions at the country level.There is a massive implementation gap in nutrition actions. For undernutrition actions we know that many countries fall far short of 90 percent coverage levels. Not enough of those who need the vitamin A, the breastfeeding promotion, the counseling on infant and young child feeding and treatment for severe acute malnutrition are getting these programs. For overweight, obesity and diabetes, the same holds true--two-thirds of all of the active programs and policies to address these issues are found in high income countries. Funding will be needed to close these gaps. Money won't solve everything--politics and capacity are important too--but it sure helps.

3. Collect data to allow us to judge how well they (the policymakers) are doing. We need data to guide actions and to hold our decision makers accountable for their actions or inaction. My kids are 13 and 14--imagine if I as a parent did not get any data on their performance in school for four years? Think of all the adjustments and support and motivation that everyone would miss out on. Well that is exactly the case with data on nutrition status and programs. We need data every year, not every four years.

Why should these decision makers do this?

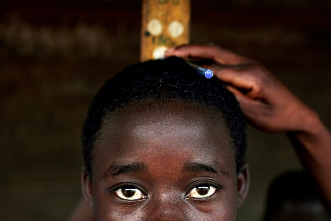

Photo: Abbie Trayler-Smith / Panos

First, they should do it for the sheer humanity of it. Malnutrition is agony. It kills. I saw an article about designer babies the other day. In the future, it will be possible to use DNA manipulation to make babies smarter, fitter and stronger. What about the ethics of it all? Well, malnutrition has the reverse effect on these things: babies' brains will develop less well and their bodies will grow more fitfully. What about the ethics of that?

If this does not move them, leaders should do it because business as usual will bankrupt their health systems. Obesity and diabetes are increasing in nearly every country in the world. Estimates of the burden placed on health systems is currently four-to-five percent in middle income countries -- what will it be in 10 years time?

And if you are an economist, you will be attracted by the returns on scaling up nutrition interventions: 16 to 1. For every rupee, peso, rand or shilling you will get 16 back. What a stellar investment opportunity!

And if you are an economist, you will be attracted by the returns on scaling up nutrition interventions: 16 to 1. For every rupee, peso, rand or shilling you will get 16 back. What a stellar investment opportunity!

The final reason why decision makers should try to improve nutrition status is that they will succeed. Countries that have done some of these things have seen dramatic declines in some major forms of malnutrition within a generation: Bangladesh, Ethiopia, Brazil, China, Vietnam and some states in India have all shown the way.

But decision makers -- whether in government, the international agencies, big NGOs, or businesses -- are all busy with lots of priorities. You and I may think ignoring nutrition is like trying to build a house on quicksand, building a tower without reinforced concrete, or setting sail with a hole in the ship's hull, but these folks are constantly distracted by events, politics, their bureaucracies and pressure groups. The status quo will inevitably prevail unless it becomes hard to defend it. We have to make it easy for those with power -- at all levels -- to act for nutrition, but also we need to make it hard for them not to do so.

So what can you do?

First, of course, help the ones you love to get what they need to improve nutrition. This is important whatever stage of life they are in but it is particularly so in the first 1000 days after conception when most of the human software and hardware is being laid down. If that is disrupted it is very hard to recover fully later in life.

Second, get political. Think like a decision maker. How can we make it easier for them to do the right thing? How can we make it harder for them to do the wrong thing, or nothing at all? That means speaking to people at schools, community groups and places of worship; writing letters to editors and parliamentarians, signing petitions, using freedom of information mechanisms, creating social media Twitterstorms, joining in peaceful protests, sharing and writing blogs and scientific articles and volunteering time to NGOs. It means educating, organizing and agitating.

Finally, don't give up. Be relentless. If decision makers make commitments at summits and then fail to implement them or even report on them, call them on it. Encourage them to be specific in what they promise. As the new Global Nutrition Report notes, too many commitments made in the name of nutrition are vague. Fuzziness is a recipe for inaction. Push pledgers to be ambitious: if they are and they fall short, assure them they will have still moved the needle and that their effort will be appreciated. They are just people like you and me. And sustain your effort. Change takes time. How quickly do you learn to do something differently? The successful countries I noted above all have seen big improvements in nutrition within a generation. But a generation means 15-20 years, not three or five. Like policymakers, you also need to think long term, but not be discouraged by that.

Finally, don't give up. Be relentless. If decision makers make commitments at summits and then fail to implement them or even report on them, call them on it. Encourage them to be specific in what they promise. As the new Global Nutrition Report notes, too many commitments made in the name of nutrition are vague. Fuzziness is a recipe for inaction. Push pledgers to be ambitious: if they are and they fall short, assure them they will have still moved the needle and that their effort will be appreciated. They are just people like you and me. And sustain your effort. Change takes time. How quickly do you learn to do something differently? The successful countries I noted above all have seen big improvements in nutrition within a generation. But a generation means 15-20 years, not three or five. Like policymakers, you also need to think long term, but not be discouraged by that.

We know what we want powerful people to do to improve nutrition. We know where and how they and others should and can do it. We just need to make it one of easiest things they ever get to do and one of the hardest things for them to avoid doing.

If we succeed, by 2025 malnutrition will no longer be viewed as one of the seemingly intractable problem facing our world.

What are you waiting for?

What are you waiting for?

This article originally appeared in the Huffington Post.

No comments:

Post a Comment